Table of Contents

Most developers optimize for extensibility. I optimize for deletion.

After a decade of maintaining enterprise applications, I’ve learned this: the quality of your design reveals itself when you try to remove code. If deletion is painful, your boundaries are wrong.

Why “Future-Proof” Code Usually Fails

You can’t predict the future. Every time you build for hypothetical requirements, you create:

- Premature abstractions that lock in decisions before you understand the problem.

- Rigid boundaries that force you to modify every layer when business logic changes.

- Fear of change because you don’t know what will break.

The real cost isn’t wasted effort. It’s code that cannot be safely deleted. When removal requires touching 15 files across different layers, you’ve built technical debt wearing a clean architecture badge.

If code is hard to delete, it’s already technical debt.

Deletion as a Design Constraint

Traditional design principles optimize for:

- Extensibility (SOLID, Open/Closed)

- Reuse (DRY, generic repositories)

- Purity (pure functions, immutability)

Delete-Driven Design optimizes for:

- Reversibility: Can I undo this decision without a major refactor?

- Locality: Does changing this feature touch only its own files?

- Safety of change: Can I delete this and know exactly what breaks?

The rule is simple:

Assume every piece of code will be deleted. Design accordingly.

Deletion tests your design in ways nothing else does. It reveals:

Coupling : What else breaks when this goes away?

Cohesion : Is related code actually together?

Boundary correctness: Did I split responsibilities at the right seams?

The Smells You Only Notice When Deleting Code

These patterns feel normal until you try removing a feature:

One feature scattered across 12 files. You delete a command handler, then hunt through validators, mappings, DTOs, view models, and Angular components spread across multiple modules.

Unrelated tests break. You remove a method from an aggregate, and suddenly unit tests for a completely different feature fail because they mock the entire object graph.

Configuration sprawl. The feature requires removing lines from appsettings.json, DI registrations in three different extension methods, and Angular provider configurations in app.config.ts.

Single-implementation interfaces everywhere. You added ICustomerValidator even though there’s only one implementation. Now it’s referenced in 20 places as a dependency, making removal a search-and-replace nightmare.

“Temporary” feature flags. You added EnableLegacyPricing two years ago. It’s now checked in 47 places, half the team doesn’t know what it does, and nobody dares remove it.

Delete-Driven Boundaries: Where Code Should Stop Knowing Things

Good boundaries make deletion local. Bad boundaries force global edits.

In C# applications with Angular frontends, I separate:

Domain logic: Business rules, validation, aggregates. Should change when business requirements change.

Application orchestration: Commands, queries, handlers. Should change when workflows change.

Infrastructure: EF Core contexts, HTTP clients, Angular services. Should change when technical implementation changes.

When I delete a feature, here’s what should happen:

Domain: Remove the aggregate. Domain events referencing it should break (good, they depend on this concept).

Application: Remove command/query handlers. Controllers or Angular components calling them should break (good, they use this workflow).

Infrastructure: Remove database tables. Migrations should show the change (good, we’re tracking state).

What should NOT break:

- Other features in the same bounded context

- Shared infrastructure (DbContext, HTTP interceptors)

- Unrelated Angular modules

If deleting this requires touching another layer, the boundary is wrong.

Example: I recently removed discount calculation logic from a multi-tenant SaaS. The deletion touched only:

DiscountPolicyaggregateCalculateDiscountCommandhandlerdiscountstable migration

The pricing module, order processing, and Angular shopping cart component required zero changes. That’s a correct boundary.

Abstractions That Prevent Deletion

Abstractions should emerge from real pain, not imagined reuse.

Interface-first design where you create ICustomerRepository before you have two implementations locks behavior too early. When business rules change, you’re stuck refactoring an interface that 12 classes depend on.

Generic repositories spread dependencies everywhere. Repository<T> sounds clean until you delete an entity and discover 8 unrelated services broke because they inject IRepository<Customer> for filtering logic that belongs in a query handler.

Extension points without consumers. You add IOrderProcessor.OnBeforeSubmit() hook for future integrations. Three years later, it’s still empty, but removing it breaks backward compatibility you never needed.

Abstractions that avoid duplication once. Two services format phone numbers identically, so you create IPhoneNumberFormatter. Now both services depend on an abstraction for 4 lines of code. Deletion requires updating DI, tests, and both call sites.

Abstractions should emerge when:

- You’ve deleted similar code twice and regretted it

- The abstraction represents a real concept in your domain

- Multiple implementations already exist in production

Not when:

- You think you might need it later

- You want “clean” architecture diagrams

- You’re avoiding duplication of trivial code

Tests as Deletion Insurance (or Deletion Blockers)

Tests should make deletion safe, not prevent it.

Tests that make deletion safe focus on behavior at boundaries:

[Fact]

public async Task ProcessOrder_WithInvalidDiscount_ReturnsValidationError()

{

var handler = new ProcessOrderHandler(_context);

var command = new ProcessOrder { DiscountCode = "INVALID" };

var result = await handler.Handle(command);

Assert.False(result.IsSuccess);

Assert.Contains("discount", result.Error.ToLower());

}

Delete the discount feature, this test breaks immediately, and that’s correct.

Tests that prevent deletion couple to implementation details:

[Fact]

public void CalculateDiscount_CallsRepository_ExactlyOnce()

{

var mockRepo = new Mock<IDiscountRepository>();

var service = new DiscountService(mockRepo.Object);

service.CalculateDiscount("CODE");

mockRepo.Verify(r => r.GetByCode(It.IsAny<string>()), Times.Once);

}

Delete IDiscountRepository, this test breaks. Delete DiscountService, this test breaks. Refactor internal implementation, this test breaks. It’s testing how, not what.

If deleting code breaks tests that don’t care about the behavior, the tests are lying.

In Angular:

// Good: tests behavior through public API

it('should disable submit button when form is invalid', () => {

component.form.patchValue({ email: 'invalid' });

fixture.detectChanges();

const button = fixture.debugElement.query(By.css('button[type="submit"]'));

expect(button.nativeElement.disabled).toBe(true);

});

// Bad: tests implementation details

it('should call validateEmail when email changes', () => {

spyOn(component, 'validateEmail');

component.form.get('email').setValue('test@test.com');

expect(component.validateEmail).toHaveBeenCalled();

});

The second test prevents refactoring validateEmail without changing a test that shouldn’t care.

Delete-Driven Design in Practice

Before: Customer notification feature spread across layers

NotificationServicewith 8 methods (email, SMS, push)INotificationRepositorywith 6 query methodsNotificationValidator,NotificationMapper,NotificationDto- Angular

NotificationModulewith 4 components - Configuration in

appsettings.json, DI registration, Angular providers

Removing email notifications required changing all of these files.

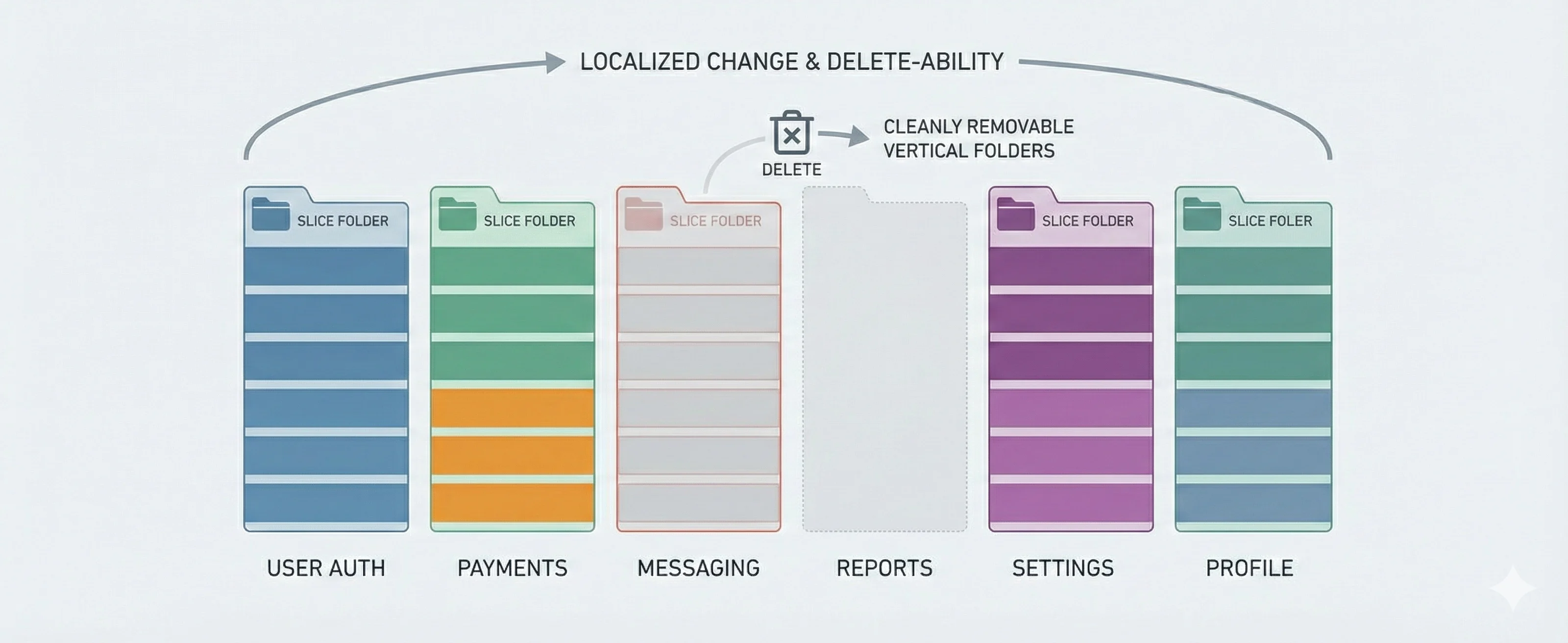

After: Customer notification feature grouped by channel

Notifications/

Email/

SendEmailCommand.cs

EmailNotificationHandler.cs

EmailTemplateRepository.cs (if needed)

SMS/

SendSmsCommand.cs

SmsNotificationHandler.cs

Push/

SendPushCommand.cs

PushNotificationHandler.cs

Angular:

notifications/

email/

email-notification.component.ts

email-notification.service.ts

sms/

sms-notification.component.ts

sms-notification.service.ts

Removing email notifications now means deleting the Email/ folder. Nothing else changes.

The shift: I stopped organizing by technical pattern (services, repositories, DTOs). I started organizing by feature. Deletion became local.

What I Optimize for Now

After maintaining applications for years, I’ve changed what I value:

Fewer public methods. If a method is public, it’s part of my API. Every public method is a deletion blocker.

Smaller interfaces. ICustomerService with 15 methods is 15 reasons I can’t delete this abstraction. I prefer multiple small interfaces over one large one.

Explicit dependencies. In Angular, I inject CustomerApiService directly, not a generic ApiService<Customer>. When I delete the customer feature, the compiler tells me exactly what breaks.

Boring, obvious code paths. Clever abstractions make deletion unpredictable. Boring code makes it obvious.

Designs that accept replacement. I don’t build systems that prevent change. I build systems where replacing major components is a planned possibility.

Good design isn’t the one that survives forever. It’s the one you can safely remove when it no longer fits.

Closing: Deletion Is the Ultimate Refactor

Refactoring improves existing code. Extension adds new capabilities. Deletion removes what’s no longer needed.

Deletion is more powerful than both. It:

- Reduces complexity permanently

- Forces you to face coupling you’ve been ignoring

- Proves whether your boundaries actually work

In practice:

Deletion > Refactoring > Extension

Reversible decisions beat elegant ones. You can’t predict what the business will need next year, but you can design code that accepts change without rewriting everything.

Simplicity shows up when things change. If you can delete a feature by removing a folder and running tests, you’ve built something maintainable.

Summary and Next Steps

Delete-Driven Design shifts focus from “what might we need” to “what can we safely remove.” The principles:

- Optimize for locality, not reuse

- Abstractions emerge from deletion pain

- Tests should verify behavior, not implementation

- Boundaries should isolate change

Related patterns to explore:

- Vertical Slice Architecture: Organizing code by feature instead of layer naturally supports deletion

- Command/Query Separation: Clear boundaries make handlers independently deletable

- Modular Monoliths: Features as modules allow deleting entire subsystems safely

- Feature Folders in Angular: Group components, services, and models by feature for localized deletion

Start small: pick one feature you wish you could delete easily. Notice what makes deletion hard. Fix those boundaries first.

References

- Delete-Driven Development

- The Art of Deleting Code

- Write Code You Can Delete

- Deleting Code is Hard

- YAGNI and Deleting Code