Table of Contents

Most EF Core tutorials stop at the fun part: you run dotnet ef database update, watch your tables materialize, and ship code. It works locally. It works in your staging environment with 10 concurrent users. Then production hits, your app scales to 5 instances, and suddenly you’re debugging why three migration attempts ran simultaneously, locked your Users table, and brought down your API.

I’ve been there. Once at 2 AM on a Friday, watching Azure App Service try to restart pods while EF Core migrations timed out because someone left context.Database.Migrate() in Program.cs. That’s when I learned: database deployment is not application deployment. They’re separate concerns that require separate pipeline stages.

This guide shows you how to deploy database migrations as a distinct, controlled step in your CI/CD pipeline using EF Core tooling, with zero downtime and production-grade security.

Why “Migrate on Startup” Breaks in Production

The pattern looks innocent enough:

// Program.cs - DON'T DO THIS IN PRODUCTION

using (var scope = app.Services.CreateScope())

{

var context = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<AppDbContext>();

context.Database.Migrate(); // Applies pending migrations

}

It works in development. It fails under load. Here’s why:

Race Conditions Kill Deployments

When your app scales horizontally (5 pods, 10 instances, whatever), they all start simultaneously. Each one tries to apply the same migration. EF Core uses the __EFMigrationsHistory table as a lock, but SQL Server’s locking behavior under high concurrency can still cause:

- Deadlocks between instances competing for the migration lock

- Timeout exceptions during schema changes on large tables

- Partial migrations if one instance crashes mid-apply

I’ve seen a 20-second migration (adding an index to a 50M-row table) timeout when 3 app instances hit it concurrently. The app never started. The deployment rolled back. The database was left in an inconsistent state.

Your App Shouldn’t Have DDL Permissions

Runtime applications should operate with least privilege. If an attacker compromises your API, they shouldn’t be able to DROP TABLE Users. But if your connection string has db_owner or db_ddladmin permissions (which Database.Migrate() requires), that’s exactly what they can do.

Production databases should use separate identities:

- Migration identity: Can alter schemas (DDL). Used only during deployment.

- Application identity: Can read/write data (DML). Used at runtime.

Azure Managed Identities and AWS IAM roles make this easy. Hardcoded admin credentials in appsettings.json make this impossible.

Startup Performance Matters

A migration that adds a foreign key constraint to a 10M-row table might take 45 seconds. Your load balancer’s health check times out at 30 seconds. Your app never reports healthy. Your deployment fails.

Even if the migration succeeds, you’ve just added latency to every cold start, every scale-out event, every container restart. Users wait. Monitoring alerts fire. Engineers panic.

The fix: Decouple database deployment from application deployment. Treat schema changes as infrastructure updates, not runtime concerns.

The Golden Rule: Idempotency

Run a migration script twice. Nothing breaks. That’s idempotency.

EF Core supports this out of the box with the --idempotent flag. Instead of generating raw SQL like:

-- Non-idempotent: crashes if column already exists

ALTER TABLE Users ADD Email nvarchar(256) NOT NULL;

It generates conditional SQL:

-- Idempotent: checks before applying

IF NOT EXISTS(SELECT * FROM [__EFMigrationsHistory] WHERE [MigrationId] = N'20240115_AddEmail')

BEGIN

ALTER TABLE Users ADD Email nvarchar(256) NOT NULL;

INSERT INTO [__EFMigrationsHistory] ([MigrationId], [ProductVersion])

VALUES (N'20240115_AddEmail', N'8.0.0');

END

Generate the script:

dotnet ef migrations script --idempotent --output migration.sql

The __EFMigrationsHistory table acts as the source of truth. EF Core checks which migrations have already run and skips them. If your pipeline retries due to a transient network error, no harm done. If you accidentally run the script twice, no harm done.

This is how you survive flaky CI/CD agents, manual interventions, and 3 AM debugging sessions where you’re not sure if the last deployment succeeded.

The Artifact Strategy: Scripts vs. Bundles

You have two options for packaging database migrations in your pipeline. Both work. One is better.

Option A: SQL Scripts

The traditional approach. Generate a SQL file during build, publish it as a pipeline artifact, execute it during release.

Build stage:

dotnet ef migrations script --idempotent --output migration.sql

Release stage:

sqlcmd -S your-server.database.windows.net -d YourDb -i migration.sql

The problem: You need sqlcmd (or equivalent) installed on your deployment agent. You need to manage connection strings, authentication tokens, and environment-specific configurations. It works, but it’s fragile.

Option B: EF Core Bundles (Recommended)

EF Core 6.0 introduced migration bundles: self-contained executables that include the EF runtime and your migration history. No SQL Server tools required. No .NET SDK required on the deployment agent.

Generate the bundle:

dotnet ef migrations bundle --self-contained --runtime linux-x64 -o efbundle

This creates a single binary (efbundle) that you can execute anywhere:

./efbundle --connection "Server=your-server;Database=YourDb;..."

Why bundles win:

- Portability: Run on any agent with the target OS. No dependencies.

- Consistency: The same binary that worked in staging runs in production.

- Security: Easier to pass connection strings as environment variables or fetch them from Azure Key Vault at runtime.

Your pipeline artifact becomes a single file instead of a SQL script plus tooling requirements.

Designing the Pipeline

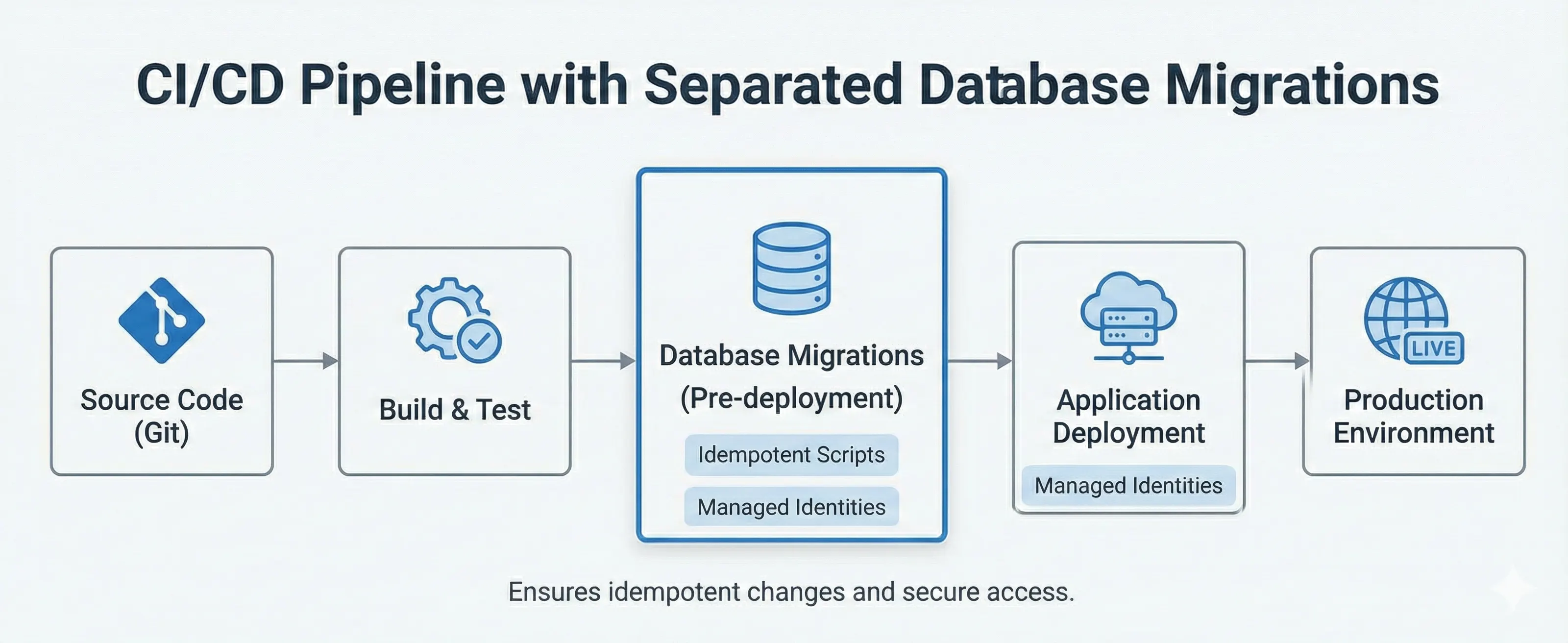

Here’s the architecture: Build generates the artifact. Release applies it before deploying the app.

Stage 1: Build (CI)

Compile code. Run tests. Generate the migration artifact. Do not touch the database.

Azure DevOps YAML:

- task: DotNetCoreCLI@2

displayName: 'Build EF Bundle'

inputs:

command: 'custom'

custom: 'ef'

arguments: 'migrations bundle --self-contained --runtime linux-x64 -o $(Build.ArtifactStagingDirectory)/efbundle'

- task: PublishPipelineArtifact@1

inputs:

targetPath: '$(Build.ArtifactStagingDirectory)/efbundle'

artifact: 'efbundle'

GitHub Actions:

- name: Build EF Bundle

run: dotnet ef migrations bundle --self-contained --runtime linux-x64 -o ./efbundle

- name: Upload Bundle

uses: actions/upload-artifact@v3

with:

name: efbundle

path: ./efbundle

The key: This stage never connects to a database. It produces a deployment-ready artifact.

Stage 2: Release (CD)

This is where the magic happens. Deploy the database first. Deploy the app second. In that order.

Step 1: Database Deployment

- task: DownloadPipelineArtifact@2

inputs:

artifact: 'efbundle'

path: $(Pipeline.Workspace)

- task: AzureCLI@2

displayName: 'Run EF Migrations'

inputs:

azureSubscription: 'YourServiceConnection'

scriptType: 'bash'

scriptLocation: 'inlineScript'

inlineScript: |

chmod +x $(Pipeline.Workspace)/efbundle

$(Pipeline.Workspace)/efbundle --connection "$CONNECTION_STRING"

env:

CONNECTION_STRING: $(DbConnectionString) # Fetched from Key Vault or pipeline variables

Step 2: Application Deployment

Only after migrations succeed:

- task: AzureWebApp@1

displayName: 'Deploy API'

inputs:

azureSubscription: 'YourServiceConnection'

appName: 'your-api'

package: $(Pipeline.Workspace)/api.zip

If the database deployment fails, the pipeline stops. Your application never deploys with an incompatible schema. This is how you avoid 500 errors at 3 AM.

Security: Managed Identities Over Connection Strings

Never hardcode connection strings in pipeline variables. Use Azure Managed Identity or AWS IAM roles.

Azure example (Managed Identity for SQL Database):

# The EF bundle connects using the pipeline agent's identity

./efbundle --connection "Server=yourserver.database.windows.net;Database=YourDb;Authentication=Active Directory Default;"

Configure the Azure DevOps service connection to use a managed identity with db_ddladmin permissions. Your app’s runtime identity only has db_datareader and db_datawriter.

This separation is non-negotiable. If your API can alter schemas, your security posture is broken.

Handling Breaking Changes: The Expand-Contract Pattern

Here’s where most teams fail. You need to rename a column from FullName to FirstName. You update the model, generate a migration, deploy. Your app crashes.

Why: During deployment, old application code (still running in some instances) expects FullName. The database just deleted it. Requests fail until all instances restart with the new code.

Even with rolling deployments, there’s a window where old code hits the new schema. You need zero-downtime schema changes.

The Solution: Expand, Migrate, Contract

Phase 1: Expand (Add the new column)

// Migration: Add FirstName, keep FullName

public partial class AddFirstName : Migration

{

protected override void Up(MigrationBuilder migrationBuilder)

{

migrationBuilder.AddColumn<string>(

name: "FirstName",

table: "Users",

nullable: false,

defaultValue: "");

// Copy data from FullName to FirstName

migrationBuilder.Sql(

"UPDATE Users SET FirstName = FullName WHERE FirstName = ''");

}

}

Deploy this migration. The database now has both columns. Old app code continues reading/writing FullName. No breakage.

Phase 2: Migrate (Update application code)

// User.cs - write to both columns during transition

public class User

{

public string FirstName { get; set; }

[Obsolete("Use FirstName")]

public string FullName

{

get => FirstName;

set => FirstName = value;

}

}

Deploy the app update. Now all writes go to FirstName. Reads work from either column. Both schemas (old and new) are compatible.

Phase 3: Contract (Remove the old column)

After confirming no rollback is needed (usually 24-48 hours):

// Migration: Drop FullName

public partial class RemoveFullName : Migration

{

protected override void Up(MigrationBuilder migrationBuilder)

{

migrationBuilder.DropColumn(

name: "FullName",

table: "Users");

}

}

Deploy the final migration. Remove the obsolete property from your model. Clean up complete.

This pattern works for any breaking change: renaming tables, changing column types, splitting entities. It requires 2-3 deployments instead of 1, but it guarantees zero downtime.

Safety Nets: Rollbacks Are a Myth

Let’s be honest: you don’t roll back database migrations in production. You fix forward.

Why rollback fails:

- Restoring a backup loses transactions (orders, payments, user registrations) that occurred between the migration and the restore.

- EF Core’s

Down()migrations are rarely tested. They might fail mid-rollback, leaving you in a worse state. - Large tables make restores slow. Your 500GB database takes 45 minutes to restore. Your SLA is 99.9% uptime. Do the math.

What you do instead:

Test on Production-Like Data

Run migrations on a sanitized clone of production before deploying. Not a 100-row staging database. A multi-GB dataset with realistic row counts and indexes.

We use Azure SQL Database’s point-in-time restore to create a staging database from last night’s production snapshot:

az sql db restore --resource-group rg-prod --server sql-prod --name db-staging --dest-name db-staging-test --time "2024-01-15T00:00:00Z"

Run the migration bundle against db-staging-test. If it takes 10 minutes on 50M rows, it’ll take 10 minutes in production. No surprises.

Use Feature Flags for Schema Changes

Decouple database changes from feature visibility. Deploy the migration (add a new Preferences table). Deploy the app (with the new feature hidden behind a flag). Enable the flag for 5% of users. Monitor. Gradually increase.

If the new feature causes performance issues, disable the flag. The database change stays (it’s expensive to revert). The feature impact stops immediately.

This is how Netflix, GitHub, and every high-scale team deploys. Schema changes are infrastructure. Feature rollout is product. They move independently.

Summary

Database migrations in production are not a runtime concern. They’re a deployment concern that requires dedicated pipeline stages, security boundaries, and zero-downtime strategies.

The rules:

- Never run migrations on application startup. Use a separate deployment stage.

- Generate idempotent scripts or EF bundles. Retries should be safe.

- Deploy database changes before application changes. The database must be forward-compatible.

- Use separate identities for migrations and runtime. Your API should never have DDL permissions.

- Plan for zero-downtime schema changes. Use Expand-Contract for breaking changes.

- Test on production-scale data. Staging databases with 100 rows don’t reveal locking issues.

- Fix forward, not backward. Rollbacks lose data and rarely work as planned.

If your current pipeline runs context.Database.Migrate() in Program.cs, audit it today. Check if your app’s connection string has db_owner permissions. If it does, you’re one SQL injection away from a dropped table.

Migrations are code. Treat them like infrastructure deployments, not application logic. Your 3 AM self will thank you.

References

Microsoft Docs: EF Core Migrations Overview

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/ef/core/managing-schemas/migrations/Microsoft Docs: Applying Migrations (EF Core Bundles)

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/ef/core/managing-schemas/migrations/applyingAzure SQL Database: Managed Identity Authentication

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/azure-sql/database/authentication-aad-overviewExpand-Contract Pattern for Zero-Downtime Deployments

https://martinfowler.com/bliki/ParallelChange.htmlGitHub Engineering: How We Deploy Database Changes

https://github.blog/2020-02-14-automating-mysql-schema-migrations-with-github-actions-and-more/Azure DevOps: Using Managed Identities in Pipelines

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/devops/pipelines/library/connect-to-azure