Table of Contents

Most engineering mistakes don’t come from ignorance. They come from good intentions applied at the wrong time.

When you’re early in your career, advice sounds absolute. “Always abstract.” “Use Clean Architecture.” “Test everything.” These principles feel like guardrails. They help you avoid obvious mistakes. But after a few years of shipping production systems, you realize they aren’t rules. They’re constraints you choose, and every constraint has a cost.

This isn’t a confession post. It’s calibration. These are the trade-offs I made with the best information I had, and what I’d do differently knowing what systems actually cost to maintain.

Over-Abstracting Before the Pain Existed

What I believed

Abstractions make systems flexible. If you anticipate change, you can design for it upfront. Future-proof architecture means introducing layers early.

What actually happened

I built interfaces with one implementation. Repository patterns wrapping Entity Framework with no actual abstraction benefit. Service interfaces that mirrored their concrete classes line-by-line.

The result? More indirection, less clarity. New developers spent time navigating layers that added zero value. When real variation finally appeared, the abstractions I’d created didn’t fit. They were guesses about future requirements, and guesses are usually wrong.

// What I wrote

public interface IUserService

{

Task<User> GetUserAsync(int id);

}

public class UserService : IUserService

{

public Task<User> GetUserAsync(int id) => _context.Users.FindAsync(id);

}

// What I should have written

public class UserService

{

public Task<User> GetUserAsync(int id) => _context.Users.FindAsync(id);

}

When the second implementation never came, that interface was just ceremony.

(Yes, there are valid reasons to abstract persistence. This wasn’t one of them.)

What I do now

Start concrete. Abstract only when variation appears in production. Let duplication exist long enough to prove the pattern before extracting it.

If I see the same logic in three places with actual behavioral differences, I abstract. If it’s copy-paste with no divergence, I leave it alone. Duplication is cheaper than the wrong abstraction.

Treat abstractions as a cost, not a virtue. Every interface is a promise that multiple implementations will exist. If that promise doesn’t materialize, you’ve added complexity for nothing.

Service Layers That Quietly Became Transaction Scripts

What I believed

A service layer means good architecture. It separates concerns. It keeps controllers thin. It centralizes business logic.

What actually happened

My domain models became anemic. Properties with getters and setters, no behavior. All the interesting logic migrated into service methods.

// Anemic domain model

public class Order

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public OrderStatus Status { get; set; }

public List<OrderItem> Items { get; set; }

public decimal Total { get; set; }

}

// Service doing all the work

public class OrderService

{

public async Task CompleteOrderAsync(int orderId)

{

var order = await _repository.GetOrderAsync(orderId);

if (order.Status != OrderStatus.Pending)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Order already processed");

order.Total = order.Items.Sum(i => i.Price * i.Quantity);

order.Status = OrderStatus.Completed;

await _repository.SaveAsync(order);

}

}

Services turned into procedural workflows. No invariants. No encapsulation. Just orchestration code that knew too much about entity internals.

What I do now

Push behavior into domain objects. An Order should know how to complete itself. Services coordinate between aggregates, but they don’t make decisions about aggregates.

public class Order

{

public void Complete()

{

if (Status != OrderStatus.Pending)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Order already processed");

Total = Items.Sum(i => i.Price * i.Quantity);

Status = OrderStatus.Completed;

}

}

public class OrderService

{

public async Task CompleteOrderAsync(int orderId)

{

var order = await _repository.GetOrderAsync(orderId);

order.Complete();

await _repository.SaveAsync(order);

}

}

Ask yourself: “What object is responsible for enforcing this rule?” If the answer is “the service,” you’re probably building transaction scripts.

Use services for coordination between bounded contexts, not for business rules within them.

Clean Architecture as a Goal, Not a Tool

What I believed

Clean Architecture equals maintainability. If you structure projects by layer (Domain, Application, Infrastructure, Presentation), you get loose coupling and testability automatically.

And to be clear: Clean Architecture absolutely helps at the right scale. My mistake was treating it as a default instead of a response to real pressure.

What actually happened

Over-segmentation. Four projects for a system that had one team and no deployment independence. Artificial boundaries that forced me to create DTOs, mappers, and interfaces just to satisfy the folder structure.

Small changes required touching multiple projects. Adding a field meant updating the domain entity, the application DTO, the AutoMapper profile, the API contract, and the database migration. Five files for one column.

The “architecture” became the product instead of serving the product.

What I do now

Start with logical boundaries, not physical ones. Use folders and namespaces before introducing separate projects.

/Domain

/Orders

/Users

/Infrastructure

/Persistence

/ExternalServices

This structure gives you the same conceptual separation without the project ceremony. When a boundary needs enforcement (maybe a second team owns Orders now), promote it to its own project.

Introduce layers when there’s team pressure or complexity pressure. Optimize for change frequency, not diagram symmetry.

If most changes stay within one bounded context, keep it together. If two teams keep stepping on each other, separate them. Architecture follows organizational reality, not UML ideals.

Premature Patterns (CQRS, Events, Pipelines)

What I believed

Using “advanced” patterns meant thinking ahead. CQRS would help if reads and writes diverged. Event sourcing would give us audit trails. MediatR pipelines would make cross-cutting concerns elegant.

What actually happened

More moving parts than business value. Debugging became harder because simple operations now involved multiple handlers, events, and projections.

// Over-engineered read/write split

public record CreateOrderCommand(int UserId, List<OrderItemDto> Items);

public record OrderCreatedEvent(int OrderId, DateTime CreatedAt);

public class CreateOrderHandler : IRequestHandler<CreateOrderCommand, int>

{

// 50 lines of handler logic, event publishing, projection updates

}

For a system doing 100 orders per day, this was solving problems we didn’t have. Cognitive load for new team members increased. Onboarding took longer because they needed to understand the pattern before they could understand the feature.

What I do now

Default to boring CRUD. Use Entity Framework. Write straightforward service methods. Ship features.

Introduce patterns only when pain is recurring and measurable. If read performance is actually bottlenecked, then consider read models. If audit requirements are complex, then look at event sourcing.

// Boring, clear, maintainable

public class OrderService

{

public async Task<int> CreateOrderAsync(int userId, List<OrderItemDto> items)

{

var order = new Order { UserId = userId, CreatedAt = DateTime.UtcNow };

order.Items = items.Select(i => new OrderItem { ProductId = i.ProductId, Quantity = i.Quantity }).ToList();

_context.Orders.Add(order);

await _context.SaveChangesAsync();

return order.Id;

}

}

Prefer reversibility over theoretical scalability. It’s easier to introduce CQRS later than to remove it once it’s embedded everywhere.

Tests That Knew Too Much

What I believed

High test coverage equals confidence. If every method has a unit test, the system is protected.

What actually happened

Tests tightly coupled to implementation. Refactoring a private method broke a dozen tests. Changing constructor parameters required updating mocks in 30 places.

// Fragile test

[Fact]

public async Task CompleteOrder_ShouldSetStatusAndCalculateTotal()

{

var mockRepo = new Mock<IOrderRepository>();

var order = new Order { Id = 1, Status = OrderStatus.Pending };

mockRepo.Setup(r => r.GetOrderAsync(1)).ReturnsAsync(order);

var service = new OrderService(mockRepo.Object);

await service.CompleteOrderAsync(1);

Assert.Equal(OrderStatus.Completed, order.Status);

mockRepo.Verify(r => r.SaveAsync(order), Times.Once);

}

This test knows about repository calls, object construction, and internal state changes. Refactor the service and the test breaks, even if behavior is identical.

What I do now

Test behavior, not structure. Focus on what the system does, not how it does it.

[Fact]

public async Task CompleteOrder_CompletesOrderSuccessfully()

{

// Arrange: test database using EF Core InMemory provider

var context = CreateTestContext();

var order = new Order { Status = OrderStatus.Pending, Items = new List<OrderItem> { new() { Price = 10, Quantity = 2 } } };

context.Orders.Add(order);

await context.SaveChangesAsync();

var service = new OrderService(context);

// Act

await service.CompleteOrderAsync(order.Id);

// Assert

var completed = await context.Orders.FindAsync(order.Id);

Assert.Equal(OrderStatus.Completed, completed.Status);

Assert.Equal(20, completed.Total);

}

This test survives refactoring. I can change the service internals and as long as orders complete correctly, the test passes.

Favor integration tests at boundaries. Use unit tests where logic is dense and isolated (like domain model methods with complex rules).

Stop measuring coverage percentage. Measure confidence in deployment.

The Meta-Lesson: Architecture Is About Constraints, Not Freedom

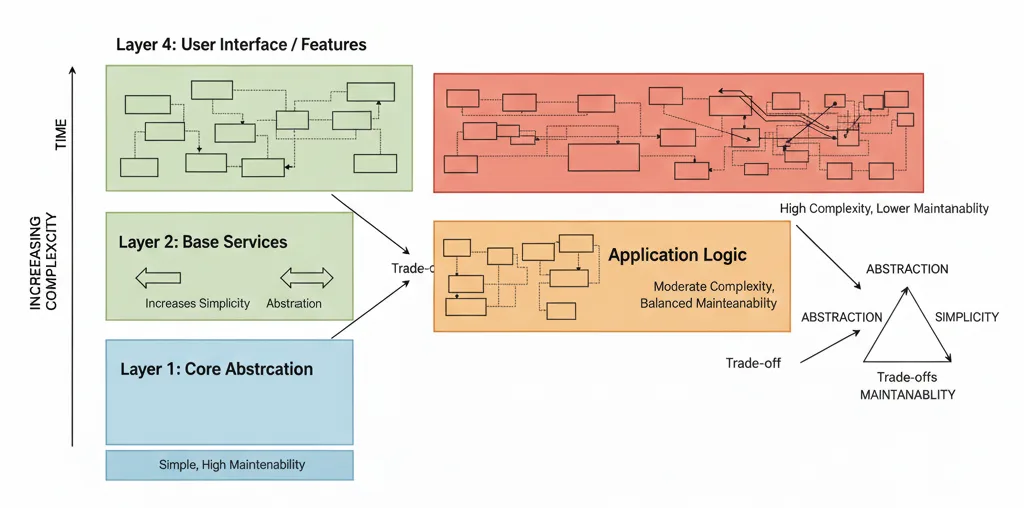

Every architectural decision removes options. When you choose Clean Architecture, you’ve constrained yourself to dependency rules and project boundaries. When you choose CQRS, you’ve constrained yourself to separate read and write models.

“Flexible” systems are often just undecided systems. They haven’t committed to constraints yet, so they feel open-ended. But that flexibility is expensive. It means more boilerplate, more indirection, more “just-in-case” code.

Good design narrows choices intentionally. It says, “We handle authentication this way,” or “We validate inputs at this layer,” and then enforces that constraint consistently.

The skill isn’t knowing more patterns. It’s knowing which constraints serve your actual system, not your imagined future system.

What I’d Tell My Past Self (and Mid-Level Engineers Today)

You don’t earn seniority by using more patterns. You earn it by knowing when not to use them.

Clarity beats cleverness. A straightforward service method that everyone understands is better than an elegant pipeline that requires explanation.

Most systems fail from overdesign, not underdesign. The CRUD app you’re embarrassed to build might run for five years with minimal maintenance. The “properly architected” system might collapse under its own complexity in six months.

Start small. Add constraints when they’re needed, not when they’re interesting.

Closing Thought

Experience isn’t about knowing more patterns. It’s about knowing when not to use them.

The best code I’ve written recently looks boring. Simple classes. Clear responsibilities. Few patterns. And it ships faster, costs less to change, and survives longer than the clever systems I was once proud of.

If I could go back, I’d spend less time designing systems for theoretical futures and more time solving actual problems. But that’s the thing about trade-offs. You only recognize them after you’ve paid the cost.