Table of Contents

Every January, the tech feed floods with prediction posts. “Top 10 frameworks to learn.” “The skills that will make you invaluable.” “Why X is dead and Y is the future.”

Most of it ages like milk.

Three years ago, it was “JAMstack or die.” Two years before that, “GraphQL will replace REST everywhere.” The cycle repeats. The predictions expire. The real problems stay.

Here’s what actually happens: frameworks change, tools evolve, but the hard problems in production software stay the same. The difference between a competent developer and a senior one isn’t knowing the latest stack. It’s knowing what compounds and what just burns time.

This post isn’t about what’s new in 2026. It’s about what still matters when the hype cycle ends.

The Illusion of “New” in Software

The industry loves novelty. New JavaScript framework. New cloud service. New architectural pattern with a catchy acronym.

But here’s the thing: most production pain in 2025 looked identical to 2015.

Systems still fail because of poor boundaries. Authorization logic still leaks everywhere. Tests still break when they shouldn’t. Database queries still tank under real load.

The tools we use to ship software change constantly. The problems that make software hard to maintain? Those are remarkably stable.

Chasing novelty feels productive. Learning React, then Vue, then Svelte, then whatever’s next gives you the dopamine hit of progress. But it rarely compounds. You’re not building judgment. You’re collecting facts that expire.

Senior developers recognize this pattern and opt out of it.

The Problems That Refuse to Die

No matter what stack you use, these show up:

Poor boundaries between domain and infrastructure

Your business logic talks directly to Entity Framework. Your controllers contain validation rules. Your services know about HTTP headers. The shape changes, but the problem doesn’t.

Accidental complexity hiding behind “clean” layers

Seven interfaces to save a record. Three mapping steps between identical DTOs. Abstractions that exist because someone read a blog post about SOLID, not because the code needed them.

Data access that scales in theory, not in production

ORMs that generate 47 queries. Lazy loading that murders performance. Transactions that lock tables for seconds. Caching strategies that work until they don’t.

Authorization smeared across the codebase

Permission checks in controllers, services, repositories, and views. Different rules in different places. Nobody knows what’s actually allowed until something breaks in prod.

Tests that slow change instead of enabling it

Brittle integration tests that fail on unrelated changes. Unit tests coupled to implementation details. A test suite that takes 20 minutes and fails randomly.

Different stacks. Same failure modes.

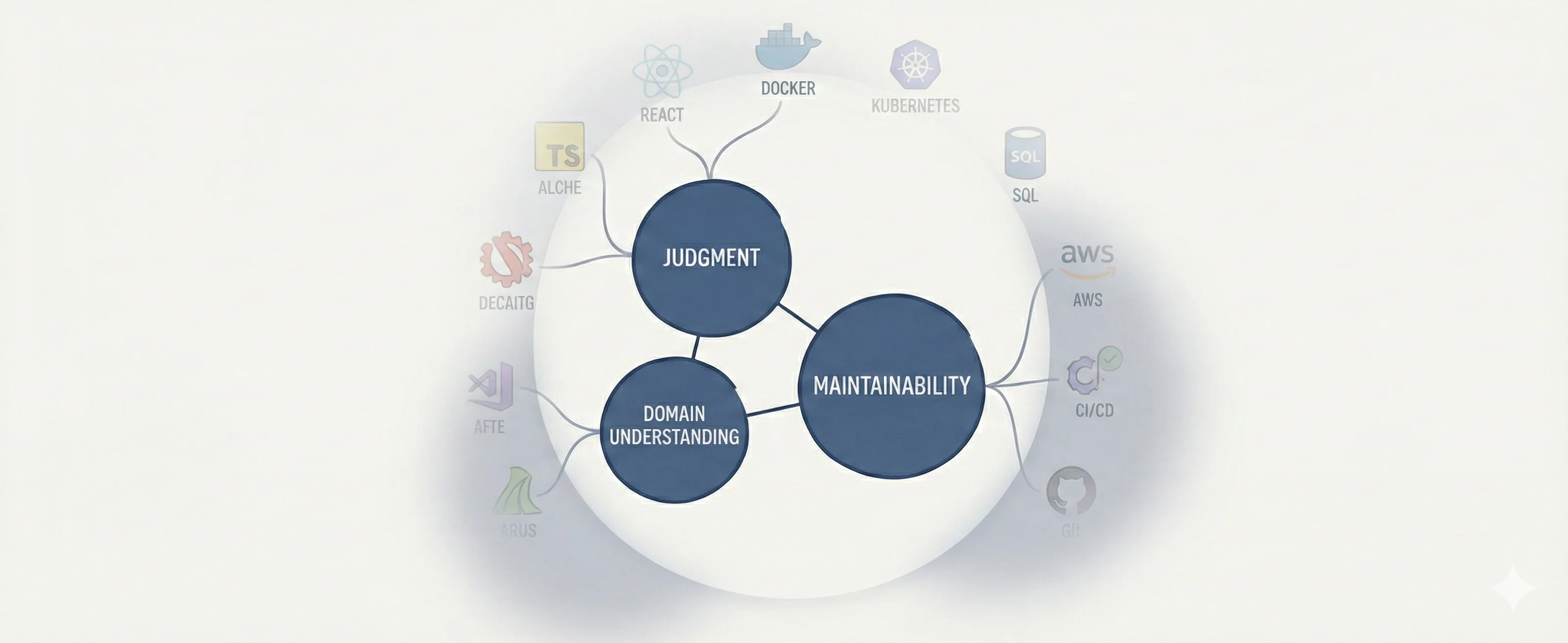

Architectural Judgment Beats Architectural Knowledge

You can memorize every Gang of Four pattern. You can explain CQRS, Event Sourcing, and Hexagonal Architecture on a whiteboard. You can cite Martin Fowler in your sleep.

None of that matters if you can’t decide when not to use it.

The cost of premature abstraction is real. CQRS in a CRUD app adds three months to delivery timelines. Microservices for a team of four turns debugging into cross-service archaeology. Event-driven architecture before you understand your domain boundaries means six months of refactoring when those boundaries shift.

These decisions feel sophisticated, but they compound badly.

Most systems don’t need more patterns. They need fewer, applied correctly.

The senior skill isn’t knowing what’s possible. It’s saying “not yet” with confidence. It’s recognizing when a simple solution will outlast a clever one. It’s understanding that architectural complexity is debt, not investment.

Here’s the test: can you explain why you didn’t use a pattern? If not, you probably shouldn’t have used it either.

Code That Can Be Changed Safely Will Always Win

Future-proof code is a myth. You can’t predict what will change. But you can write code that’s easy to change when the time comes.

Maintainability beats cleverness every single time.

The code that survives isn’t the code that anticipated every possible future. It’s the code that made local reasoning easy. Small functions with clear names. Explicit dependencies instead of hidden magic. Data structures that match the domain, not the database.

When you write code, ask: How hard would it be to delete this?

If the answer is “I’d have to trace through six layers and update four different config files,” you’ve built a trap. Code that’s hard to remove is code that resists change. And software that resists change becomes legacy software, no matter how clean it looked on day one.

Delete-ability is a design metric. The best code I’ve written wasn’t the most elegant. It was the code I could rip out and replace in an afternoon when requirements shifted.

Domain Modeling Is Still the Highest-Leverage Skill

Anemic domain models are everywhere. POCOs with getters and setters. Services that contain all the logic. Controllers that orchestrate everything.

It’s not laziness. It’s that modeling actual business behavior is hard.

Most developers can translate a database schema into C# classes. That’s not domain modeling. That’s data modeling.

Real domain modeling means thinking in invariants, not DTOs. It means asking: what rules can’t be broken? What states are invalid? What operations make sense together?

When you get this right, the rest of the system gets easier. Controllers get thin. Services get focused. Tests get clearer. Authorization becomes a natural boundary, not an afterthought.

When you get it wrong, you spend years fighting the code. Logic scatters across layers. Every feature requires touching ten files. Nobody trusts the system to enforce its own rules, so validation happens everywhere and nowhere.

Clean code starts with correct behavior. Everything else is formatting.

Performance Work Is Back (And It’s Mostly Boring)

For a decade, “fast enough” was good enough. Cloud resources were cheap. Scaling horizontally solved most problems. Performance optimization felt like premature work.

That’s changing.

Cloud costs are squeezing budgets. “Scale up” isn’t a free answer anymore. Teams are getting pressure to reduce bills, which means caring about performance again.

But here’s the thing: most performance work isn’t sexy. It’s not fancy caching strategies or cutting-edge algorithms. It’s:

- Adding the right index to SQL Server

- Fixing N+1 queries that your ORM hides

- Understanding why your API allocates 2GB per request

- Knowing when to use

AsNoTracking()in EF Core (or understanding your ORM’s unit-of-work cost model) - Actually profiling instead of guessing

Seniors optimize by understanding, not benchmarking blindly. They know the cost model of their stack. They can explain why a query is slow by looking at the execution plan. They fix the right bottleneck, not the obvious one.

Performance isn’t about making everything fast. It’s about making the right things fast enough, consistently.

Testing That Protects Change, Not Ego

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: most test suites slow teams down.

Not because testing is bad. Because the tests are testing the wrong things.

Integration tests that break when you rename a class. Unit tests that mock six dependencies to test one line. Tests that pass in isolation but fail when run together. Suites that take 30 minutes because someone thought “more coverage = better quality.”

Good tests enable refactoring. Bad tests prevent it.

The best tests I’ve written are boring. They exercise behavior, not structure. They fail when the contract breaks, not when the implementation changes. They’re fast enough to run constantly, reliable enough to trust, and clear enough that failures point directly to the problem.

Fewer tests, higher confidence. That’s the goal.

If you can’t refactor without breaking tests, your tests are coupled to the wrong things. Fix the tests, not your refactoring approach.

Communication Is Now a Core Technical Skill

The hardest part of senior work isn’t writing code. It’s explaining why the code should be written that way.

You’ll spend more time in documents, architecture reviews, and design discussions than you will in your editor. And most of those conversations happen with people who don’t read C#.

Can you explain trade-offs to a product manager?

Not in terms of SOLID principles or design patterns. In terms of risk, cost, and time.

Can you write a design doc people actually read?

One page that captures the decision, the alternatives considered, and the consequences. Not a 20-page PDF that nobody opens.

Can you make architectural decisions reversible?

By documenting why you chose option A over B, so the team can revisit it later with context instead of assumptions.

Seniors reduce confusion before writing code. They make decisions visible. They communicate in the language their audience understands.

The best technical decisions are the ones non-technical stakeholders can reason about too. When you can explain a technical trade-off in terms that build trust instead of confusion, you multiply your impact beyond code.

What I’m Personally Doubling Down On in 2026

Here’s what I care about this year:

Better boundaries, fewer layers

Stop adding abstractions because they “might be useful.” Add them when the pain of not having them is clear.

Smaller, clearer APIs

Every public method is a promise. Every dependency is coupling. Reduce both.

Tests that enable refactoring

If I can’t change the implementation without breaking tests, the tests are wrong.

Saying “no” more often, and earlier

To premature patterns. To clever solutions. To features that don’t align with the domain.

Teaching through real production examples

Theory is easy. Showing what actually failed, why it failed, and how we fixed it, that’s harder. But that’s what compounds.

I’m done chasing frameworks. I’m done with “best practices” that ignore context. I’m focused on the boring, compounding work: clear code, correct models, and decisions that age well.

Closing Thought

Senior developers don’t optimize for elegance. They optimize for change.

Seniority isn’t about knowing more tools. It’s about needing fewer of them.

In 2026, I’ll care less about what’s new and more about what works. Less about architectural purity and more about code that can change safely. Less about following best practices and more about understanding trade-offs.

The skills that compound aren’t the ones that look good on a resume. They’re the ones that prevent 3 AM incidents, enable safe refactors, and let you sleep at night knowing the system won’t surprise you.

That’s what I’m building toward. Not perfection. Just software that does its job and doesn’t fight you when it needs to change.

Related posts you might find useful:

- The Real Difference Between Domain and Application Layer

- Avoid Anemic Domain Models (And Why They Keep Happening)

- The Clean Code Rules I Wish I Knew Sooner