Table of Contents

The service layer promised to clean up our code. It was supposed to coordinate use cases, encapsulate business logic, and keep controllers thin. Instead, it became the dumping ground for everything that didn’t fit cleanly into a controller or repository.

I’ve written services with 12 constructor dependencies. I’ve seen ApproveOrderService, ProcessPaymentService, and ValidateUserService classes that each did one thing but needed half the application injected to do it. The tests were nightmares. The refactorings took weeks.

The problem isn’t the service layer. It’s treating it as a safe place to hide decisions.

The Promise of the Service Layer (And Why It Sounds Right)

When you first learn about service layers, they make perfect sense. Every tutorial shows them. Every Clean Architecture diagram includes them. They sit between your controllers and your data, orchestrating the work.

The pitch is compelling:

- Controllers stay thin and focused on HTTP concerns

- Business logic lives in one place instead of scattered everywhere

- You can test logic without spinning up a web server

Early in a project, this works. You create UserService, wire up dependency injection, and life is good. Controllers call services, services call repositories, and everyone’s happy.

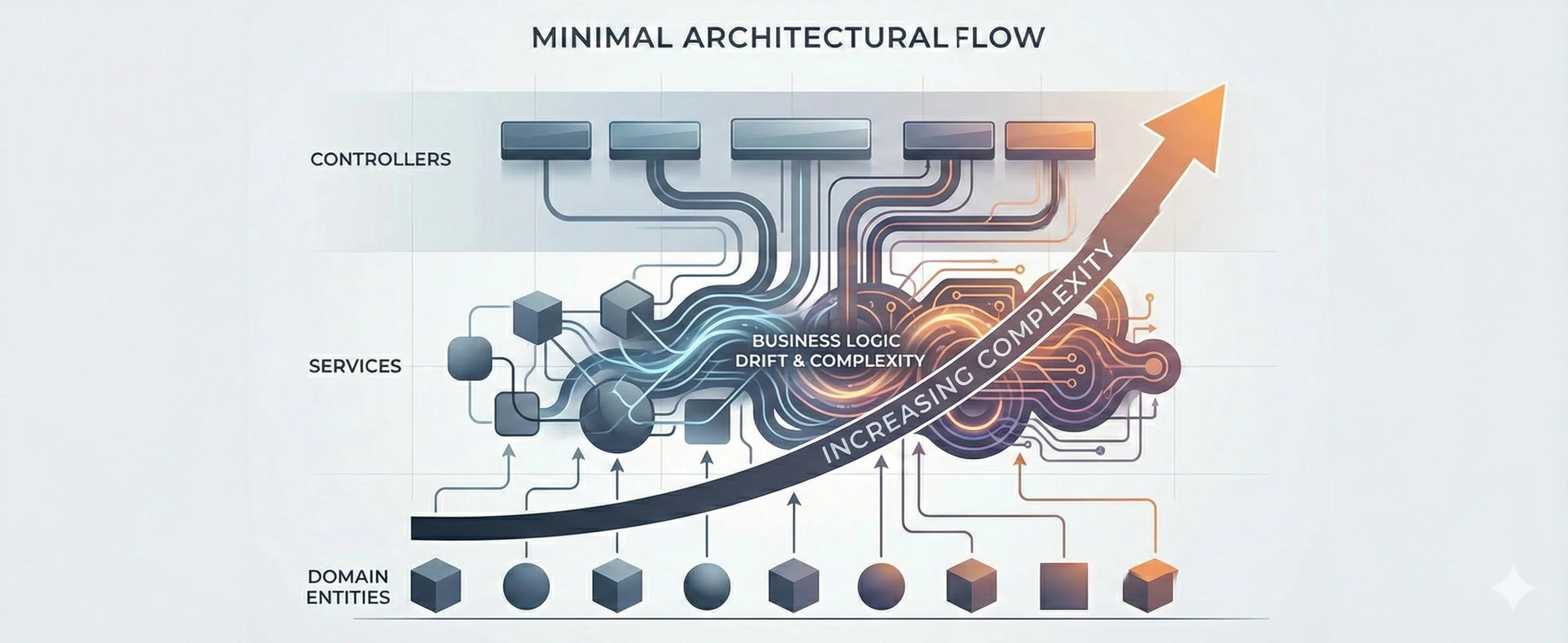

Then the project grows. You add CreateUserService, UpdateUserService, DeleteUserService, ActivateUserService, DeactivateUserService. Each one does exactly what its name suggests. Each one feels clean and single-purpose.

What you’ve built is a transaction script with better naming.

The Transaction Script Smell Nobody Talks About

Look at a typical service method:

public async Task<Result> ApproveOrder(int orderId, int approvedBy)

{

var order = await _repository.GetById(orderId);

if (order == null) return Result.NotFound();

if (order.Status != OrderStatus.Pending)

return Result.Invalid("Only pending orders can be approved");

if (order.TotalAmount > 10000 && !await _userService.IsManager(approvedBy))

return Result.Unauthorized("Large orders require manager approval");

order.Status = OrderStatus.Approved;

order.ApprovedBy = approvedBy;

order.ApprovedAt = _clock.UtcNow;

await _repository.Update(order);

await _notificationService.NotifyCustomer(order.CustomerId, "Order approved");

return Result.Success();

}

This passes code review. It’s testable. It’s explicit about its dependencies. But it’s a procedural function that directly manipulates data structures.

The symptoms are consistent:

- Long methods that read like a recipe

- Multiple dependencies injected just to check conditions

- Branching logic based on entity state

- Direct mutation of entity properties

This is what Martin Fowler called a transaction script in 2002. We just moved it from controllers into services and declared victory.

How Service Layers Create Anemic Domain Models

Here’s what happens next. Your Order entity looks like this:

public class Order

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public OrderStatus Status { get; set; }

public decimal TotalAmount { get; set; }

public int? ApprovedBy { get; set; }

public DateTime? ApprovedAt { get; set; }

}

It’s a data structure with getters and setters. All the behavior lives in services. The entity can’t protect itself.

Want to approve an order? Call ApproveOrderService. Want to cancel it? Call CancelOrderService. Need to validate that an order can be shipped? Write that logic in ShippingService.

The consequences compound:

- Nothing stops you from setting

Status = OrderStatus.Approvedwithout settingApprovedBy - Validation rules get duplicated across services

- Invariants exist only as comments or tribal knowledge

I’ve debugged production issues where orders were in impossible states because some service bypassed the approval logic and just set the status directly. The entity had no way to defend itself.

This is the anemic domain model Martin Fowler warned about. We created it by moving all behavior up into services.

Orchestration != Business Logic (This Is the Core Mistake)

The fundamental confusion is this: orchestration and business logic are different things.

Orchestration is coordinating steps:

- Starting a transaction

- Calling multiple aggregates in sequence

- Publishing events to external systems

- Managing cross-cutting concerns like logging

Business logic is making decisions:

- Can this order be approved?

- What’s the discount for this customer?

- Is this state transition valid?

Services should handle orchestration. Entities should handle decisions.

When you put decision logic in services, you’ve inverted the dependency. Your domain model depends on application services to know what’s valid. That’s backwards.

Here’s what orchestration actually looks like:

public async Task<Result> ProcessOrder(int orderId)

{

using var transaction = await _unitOfWork.BeginTransaction();

var order = await _orderRepository.GetById(orderId);

var result = order.Process(_clock.UtcNow); // domain logic lives here

if (!result.IsSuccess)

return result;

await _orderRepository.Update(order);

await _eventBus.Publish(new OrderProcessedEvent(orderId));

await transaction.Commit();

return Result.Success();

}

The service coordinates persistence and messaging. The entity decides what “processing” means. Each does what it’s good at.

The Dependency Explosion Problem

Look at a typical service constructor after six months:

public class OrderService

{

private readonly IOrderRepository _orderRepository;

private readonly IUserRepository _userRepository;

private readonly IInventoryService _inventoryService;

private readonly IPaymentService _paymentService;

private readonly INotificationService _notificationService;

private readonly IDiscountCalculator _discountCalculator;

private readonly IShippingCalculator _shippingCalculator;

private readonly ITaxCalculator _taxCalculator;

private readonly IClock _clock;

private readonly ILogger<OrderService> _logger;

public OrderService(/* inject all 10 dependencies */) { }

}

Ten dependencies to save an order. Every method uses a different subset of them. Tests require mocking half the application.

This signals that logic is in the wrong place. If your service needs IDiscountCalculator, that’s because discount logic should be in Order.CalculateDiscount(). If it needs IInventoryService, that’s because inventory checks should happen in Order.ReserveItems().

The dependency explosion is a symptom. The disease is putting domain decisions in application services.

I’ve worked in codebases where adding a new field to an entity required touching seven services. Not because the feature was complex, but because every bit of logic that touched that entity was scattered across the service layer.

Why Service Layers Make Testing Harder, Not Easier

The selling point of service layers is testability. In practice, they make testing worse.

A test for ApproveOrderService has to:

- Mock the repository to return an order

- Mock the user service to return permissions

- Mock the notification service to verify it was called

- Mock the clock to control time

- Assert on the specific sequence of calls

That’s not a behavior test. That’s a contract test for implementation details.

When you refactor, these tests break. Not because behavior changed, but because you reordered steps or renamed a method. The test suite becomes an anchor.

Compare this to testing domain behavior:

[Fact]

public void CannotApprove_WhenAlreadyApproved()

{

var order = Order.CreatePending(amount: 1000);

order.Approve(approvedBy: 1, approvedAt: DateTime.UtcNow);

var result = order.Approve(approvedBy: 2, approvedAt: DateTime.UtcNow);

Assert.False(result.IsSuccess);

}

No mocks. No setup. Just the rule being tested. When you refactor internal implementation, this test still passes because it targets behavior, not mechanics.

Service layer tests are brittle because they test orchestration mixed with rules. When you separate concerns, you can test rules without mocking infrastructure.

When a Service Layer Actually Makes Sense

Service layers aren’t evil. They’re misused.

Here’s when you actually need them:

Application services coordinating multiple aggregates:

public async Task<Result> CompleteCheckout(CheckoutCommand command)

{

var cart = await _cartRepository.GetById(command.CartId);

var order = cart.ConvertToOrder(_clock.UtcNow);

var payment = await _paymentGateway.Charge(order.Total);

order.RecordPayment(payment);

await _orderRepository.Save(order);

await _cartRepository.Delete(cart);

return Result.Success(order.Id);

}

This service coordinates cart, order, and payment. It doesn’t decide order rules. It orchestrates the workflow.

Cross-boundary workflows:

When you’re integrating with external systems, wrapping retries, or managing distributed transactions, application services make sense. They handle things that don’t belong in your domain model.

Long-running or async processes:

Background jobs, batch processing, scheduled tasks. These need coordination logic that sits outside your core domain.

Red flags that you’re doing it wrong:

if/elsebranches based on entity state- Validation logic that duplicates business rules

- Methods that directly mutate entity properties

- Constructor dependencies that are really domain policies

If your service has conditional logic, ask yourself: should this condition be enforced by the entity?

A Better Mental Model: Behavior Lives With Data

The shift is simple: entities should own their behavior.

Instead of:

public class OrderService

{

public Result ApproveOrder(Order order, int approvedBy)

{

if (order.Status != OrderStatus.Pending)

return Result.Invalid();

order.Status = OrderStatus.Approved;

order.ApprovedBy = approvedBy;

return Result.Success();

}

}

Do this:

public class Order

{

public Result Approve(int approvedBy, DateTime approvedAt)

{

if (_status != OrderStatus.Pending)

return Result.Invalid("Order must be pending");

_status = OrderStatus.Approved;

_approvedBy = approvedBy;

_approvedAt = approvedAt;

return Result.Success();

}

}

The entity protects its invariants. The service just calls methods:

public async Task<Result> ApproveOrder(int orderId, int approvedBy)

{

var order = await _repository.GetById(orderId);

var result = order.Approve(approvedBy, _clock.UtcNow);

if (result.IsSuccess)

await _repository.Update(order);

return result;

}

This reduces:

- Duplication (approval logic exists in one place)

- Test surface area (test the domain method directly)

- Cognitive load (no wondering where rules live)

Here’s a heuristic: if it changes the state, it probably doesn’t belong in a service.

State transitions are domain behavior. Services coordinate. Entities decide.

Why This Keeps Happening (Even on Senior Teams)

If this pattern is so flawed, why do experienced developers keep building it?

Fear of fat entities: We’ve been told entities should be “simple.” Putting behavior in them feels like code smell. So we move it to services and call it clean.

ORM leakage: EF Core requires public setters for navigation properties. Developers see public set and assume entities should be data bags.

Misapplied Clean Architecture diagrams: Diagrams show a service layer. We build one. We never ask what should go in it.

Junior devs copying senior patterns: A junior sees UserService, so they create ProductService. The pattern spreads through cargo cult.

Seniors optimizing for review safety: It’s easier to get approval for “just another service” than to explain why an entity should have methods.

I’ve done all of this. I created service layers because they felt professional. I moved logic up because it seemed cleaner. I only stopped when I spent three months refactoring a codebase where every change touched 14 services.

What I Do Instead Today

I still use application services. But I’m ruthless about what goes in them.

Services handle orchestration:

- Starting transactions

- Publishing domain events

- Calling external APIs

- Coordinating multiple aggregates

Entities handle decisions:

- State transitions

- Validation rules

- Business calculations

- Invariant enforcement

When I’m not sure where logic belongs, I ask: does this decision require knowledge from outside the entity?

- If yes, it might belong in a service

- If no, it definitely belongs in the entity

Example: calculating a discount might need customer tier information from another aggregate. That could be a domain service. But deciding if an order can be canceled only needs the order’s state. That’s an entity method.

I still make mistakes. I catch myself putting conditional logic in services when it should be in entities. The difference now is I recognize the smell and refactor before it spreads.

Services That Coordinate vs Services That Decide

The turning point is recognizing this: when services make decisions, your domain becomes a data structure, and your system slowly forgets what it’s supposed to protect.

Service layers aren’t the problem. Misusing them as transaction scripts is.

Build thin services that orchestrate. Build rich entities that decide. Keep the distinction clear, and you won’t need a service for every database operation.

If You’re Stuck With This Today

If you’re dealing with service layers that have grown out of control, start here:

- Identify services with heavy conditional logic and move those rules into entity methods

- Look for validation that happens in multiple places and consolidate it into the entity

- Review your entities for public setters that bypass invariants

- Check out domain-driven design patterns like Aggregates and Value Objects for better ways to model behavior

Related patterns that help:

- Rich domain models (entities with behavior, not just data)

- Domain events (for cross-aggregate coordination without service coupling)

- Specification pattern (for complex business rules that need reuse)

The goal isn’t to eliminate services. It’s to stop using them as dumping grounds for everything that isn’t a controller.

References

- Catalog of Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture

- Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture (Book Page)

- Service Layer Pattern Discussion

- Anemic Domain Model Anti-Pattern